Wonolo

Recently, I was invited by Unum, one of our FORTUNE 500 customers, to participate in a panel session about corporate innovation at Maine Startup and Create Week. At the heart of our discussion was how large companies like Unum can be more innovative and how startups and large companies can work together toward this goal.

It’s a topic that’s close to my heart: I spent the first part of my career in the wireless industry, and back in 1998, I was a part of the founding team of Symbian, one of the first operating system platforms for smartphones (although they weren’t yet called “smartphones” at that point).

Symbian was a joint-venture between Nokia, Ericsson, Motorola, Psion, Panasonic and, later, several others. Their rationale for investing in Symbian was a desire to have a common software platform for smartphones. However, what these companies actually had in common was that they were large, bureaucratic, and they were arch-competitors.

Getting these large companies in the Symbian joint-venture to work together was somewhere between very hard and impossible. (For the full story, see David Wood’s excellent book.) The term of art at the time was term “coopetition,” and it didn’t work. None of the participants in Symbian really had any desire to share their product plans with their competitors.

So, the irony was that, while Symbian was arguably at the spearhead of technology innovation, it was frequently stymied from actually being innovative by the inertia and culture of its participants. This left the market open to more focused, agile and independent companies like Google and Apple to dominate the smartphone market of today. In contrast, Nokia had an ignominious end – broken up and sold off, with billions of dollars in market value destroyed.

So, fast-forward to 2016 and my panel discussion at Maine Startup and Create Week…How can big companies be more innovative, and how can startups and large companies work together to the benefit of both?

Designer, Builder or Maintainer?

First, let’s take a look at the kinds of people that tend to work at startups versus larger companies: I have a simplistic but hopefully powerful model that divides people into three groups – “designers,” “builders” and “maintainers.”

Let’s use an analogy: here in San Francisco, arguably our best-known symbol is the Golden Gate Bridge – just look at any tourist tchotchke.

If we think about the Golden Gate Bridge, first there were the designers. In our culture, the designers generally have the “sexy” job – they are the visionaries.

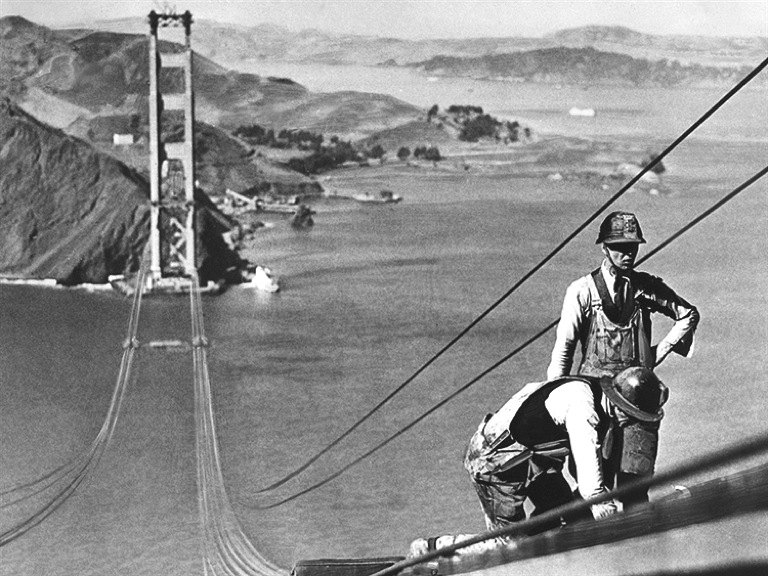

Next come the “builders” who actually constructed the Golden Gate Bridge.

Last come the “maintainers.” These are the workers who hang on ropes off the bridge, scraping off rust and continuously repainting it in International Orange.

This is the least sexy job in most people’s eyes: Which would you rather be – the visionary designer of the Golden Gate Bridge or someone who hangs off it on a rope, scraping rust?

Now, in a startup, what you need for success are just a few designers – these are typically the founders. You can’t have too many because they tend to butt heads.

What you really need for a startup is a boat-load of builders: these are the doers – people that create and get sh*t done (GSD). Builders are the backbone of any startup.

What you don’t need in a startup is maintainers: everything in a startup is being created anew so there isn’t anything to maintain. You’re also focused on growth rather than optimization.

Contrast that to a big, established company: there, most people are maintainers. Their job is to ensure that an already successful business continues to be more successful. They are there to grease the wheels and optimize.

So What?

What this means is that there is a cultural mismatch between a large company and a startup.

At the core of the startup mindset is a willingness to fail and an acceptance of it. In a startup, failure is the norm – as the cliché goes, you fail your way to success. Since “failure” has negative connotations, I think it better to simply reframe it as “learning.”

Another important aspect of building a startup is understanding the art of the “good enough.” Because you’re bandwidth-constrained, you are forced to be very selective and very efficient in how you do things. You have to get them done quickly. You have to not let the great be the enemy of the good. You have to focus on delivering 80% of perfection for 20% of the effort.

Naively, when large companies aspire to become more innovative, they trot out clichés like “we reward risk-takers.” This is a lie. The last thing you want when you have a large company generating billions in revenue it to have some cowboy risk-taker come in and break it. What you want are maintainers to keep it working and keep it generating billions of dollars.

To take it back to the Golden Gate Bridge example, would you want a maintenance worker who said, “Let’s see what happens if we take all the bolts out”?

I think it would be better to rephrase it as, “We reward people who make small, smart bets.” Making a series of small, smart bets to test various hypotheses is the basis of iteration, and iteration is the how you build great products and great companies.

Recognizing these problems, many large companies have started to take a different approach – they have created specific initiatives intended to foster and drive innovation. Wonolo itself was created through The Coca-Cola Company’s innovation program.

Creating a Great Corporate Innovation Program

So, how can a large company create an innovation group and/or program likely to succeed? These initiatives can take various forms, but I think these are the most important elements:

- Set money aside – the budget for innovation can’t come out of the normal, operating budget for any existing business unit. If it does, it competes with the budget needed for maintenance of what’s already working.

- The innovation group must report directly into the CEO – this demonstrates genuine commitment to innovation and also helps unblock bureaucracy.

- Be clear with objectives – what specifically are you hoping that the innovation program does for your business? What are you looking to achieve? How does it positively impact your core business?

- Build the right team – a good mix is designers and builders from outside of the organization, along with some inside players who can help navigate the existing organization, as long as they carry enough weight. You will also need to reassure your best maintainers that they should stick to what they do well rather than trying to join the innovation program because it’s sexy.

- Accept failure – as discussed above, you must accept that failure is a vital part of the process. Not all initiatives you start or companies you fund will be successful, but you will learn something important from each.

How Can a Startup Engage with a Big Company and Win?

Big companies can kill startups. I’ve seen it happen.

Big companies can lead startups on and consume lots of their time and bandwidth with no pay-day. At the end of the process, the large company has perhaps lost a few hundred thousand dollars. Meanwhile, the startup has run out of funding and is dead.

Here’s what I’ve learned (the hard way) to avoid that outcome:

- Find your champion. Ted Reed is our champion at Unum. Not only is he an all-round great guy, but he also understands the need to be completely transparent with us. A great champion is your guide to the large company – its structure, how it makes decisions and the key players you’ll need to win over.

- Seek trust, honesty and transparency – any great relationship is built on mutual trust. Get feedback early and often (from your champion) on your likelihood to succeed.

- Don’t over-invest until you have clear commitment – be prepared to scale back or end the relationship if it’s not clear you are on a path to success. The opportunity cost of your time in a startup is huge. Don’t do anything for free – free means there’s no value, and it won’t be taken seriously.

- Ensure clarity in objectives, value and define success – if both sides are not clear on the business value that your product or service is providing to the large customer, be very cautious. Make sure both sides agree on what success means.

- Start with a small, well-defined trial – rather than trying to boil the ocean, it’s wise to start with a trial that demonstrates the value your product or service provides to the large company. This has less risk, requires less investment and has a higher likelihood of success. For more tips on how to best go about setting up a pilot, check out our related blog post.

How Can a Big Company Engage with a Startup and Win?

On the other side, how can big companies successfully engage with startups and win? Here’s my personal recipe:

- Be honest and transparent – don’t lead startups on. Be honest about chances of success and what it will take.

- Be respectful of bandwidth and provide funding, if possible – realize that a startup’s most precious commodities are bandwidth and funding. Do everything you can to reduce the sales cycle. Structure the deal to provide the funding and/or revenue necessary for the startup to succeed.

- Have realistic expectations in terms of maturity of a startup and its processes -don’t try to apply your pre-existing vendor onboarding process when engaging with a startup. For example, a 10-person startup won’t pass your 50-page IT security audit.

- Respect the need for independence – you may be providing a startup with revenue, funding and a great customer reference. However, a startup needs to be in control of its own destiny and own its own product roadmap. Don’t treat a startup like a consulting company or development shop, unless that’s how the startup sees themselves.

Overall, the relationship between a large company and a startup can be a marriage made in heaven. I would marry Ted Reed if I could.